By Yonat Shimron, Raleigh News & Observer

By the time H. Shelton Smith was hired to teach at Duke University in 1931, the movement to unite Christians of different denominations was under way in New York and other places.

But four years later when Smith founded the N.C. Council of Churches, the idea that Christians of various stripes could work together, especially in overcoming racial segregation, was still largely unheard of in the South.

Today, the N.C. Council of Churches is marking 75 years of activism on a broad range of issues, including racial equality, women’s empowerment, children’s health care, prison reform, farmworker rights and environmental conservation.

“Starting an ecumenical organization in the Southern United States was a pioneering thing,” said the Rev. Collins Kilburn, a retired director of the council. “The sectarian spirit was strong in the South.”

Then as now, not all churches were part of the effort. The Baptist State Convention of North Carolina briefly signed on in 1935, but Baptists, the state’s largest religious group, quickly backed out and were never again part of the council. Neither were most Pentecostal groups.

But Episcopalians, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, Roman Catholics and some black Baptist and Methodist groups formed the backbone of the council and continue to work on “social justice” issues.

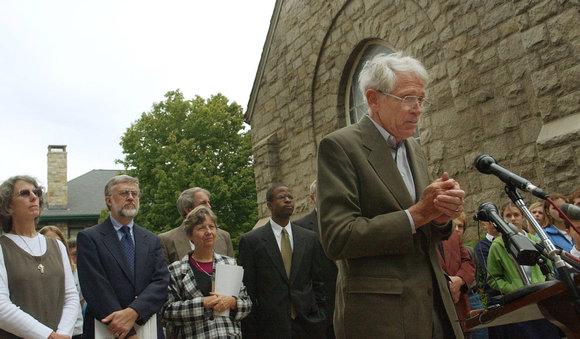

At an anniversary celebration last week at Duke, those active with the council heard about its signal achievements as well as its failures. (Remember the Equal Rights Amendment, which would have enshrined the rights of women in the U.S. Constitution? The council fought for the amendment only to see it fail to gain ratification.)

“The Council of Churches wasn’t interested in giving comfort – it was more of a prophet, a sharp tool in the bag, prying and calling for change,” said the Rev. Vernon Tyson of Raleigh, a retired Methodist minister and leader in the fight against segregation, and the protagonist in the book “Blood Done Sign My Name.”

But the council’s moment of fame came on a much less predictable issue. In 1982,with famine raging in Ethiopia, the council’s hunger task group came up with the idea of studying the possibility of converting tobacco farmland in North Carolina for food cultivation.

The Tobacco Study Committee called on farm, manufacturing and medical experts to investigate the issue and in November 1983, held a public hearing in Raleigh.

“We were totally unprepared for the media coverage we got,” said the Rev. Rufus Stark, a retired Methodist minister who led the committee. “All of a sudden, it was national news.”

Reporters from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, National Public Radio and the three major TV networks were eager to tell the story of a church coalition ready to take on tobacco.

It wasn’t as though the council’s tobacco committee was calling for the wholesale uprooting of a way of life.

“We weren’t interested in being judgmental,” Stark said. “We recognized that all of us in Eastern North Carolina are beholden to tobacco culture. We all benefited from it.”

Still, the willingness to investigate alternative solutions to what was becoming a well-known public health hazard was big news.

That willingness has been the council’s chief strength. While other religious groups such as the Christian Action League were focused on a narrow set of issues such as alcohol or gambling, the council showed it was willing to tackle larger public concerns methodically and thoughtfully.

“I think it continues to have the same presence at the legislature,” said the Rev. Jimmy Creech of Raleigh, a former Methodist minister who worked for the council from 1991 to 1996. “The Council of Churches has always focused on public policy issues rather than a particular religious or theological point of view, and it continues to be respected for that.”

The council has lost some of its clout with the decline among mainline Protestant denominations and younger Christians flocking to nondenominational congregations and megachurches. But the council – which gave birth to advocacy groups such as People of Faith Against the Death Penalty, the Triangle AIDS Interfaith Network and the Covenant with North Carolina’s Children – sees a continued place for its work.

And its leaders are unwilling to cede the mantle on important issues. Recently, it published an eight-week study guide on immigration titled “For You Were Once a Stranger” that attempts to offer a biblical understanding of the role of immigrants. It created N.C. Interfaith Power and Light, one of 31 state initiatives intended to help people of faith take up environmental concerns. And it has taken on the obesity epidemic with its health and wholeness program targeted to African-American churches, where obesity and diabetes are more prevalent.

Council members also know they cannot win every battle. “Often the best cause in the world is a lost cause,” Tyson said. “The N.C Council of Churches knows about lost causes.”