Our country’s annual salute to the memory of Martin Luther King Jr. honors him as the foremost crusader in the grand civil rights movement of the mid-20th century – the movement that finally broke the shackles of legally imposed racial segregation.

What King and his countless allies sought was simple enough, at least in principle. They wanted equality of opportunity, giving black Americans – and by extension all minorities on the receiving end of prejudice – a fair shot at sharing in our national blessings. They wanted a society in which, as King famously put it, people are judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

King’s role as a Baptist minister and head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference dramatized the link between the drive for civil rights and the scriptural call for justice.

White Americans were challenged to stop treating their black fellow citizens as inferior not only because the Constitution, if taken at its word, required it, but also because oppression of the poor and the weak ran afoul of core Judeo-Christian teachings.

The civil rights movement engaged the leading mechanisms of discrimination: segregated schools, segregated public facilities, racial bias in the workplace and in the courts. The means were relentless but nonviolent – sit-ins, boycotts, marches. The first great chapter reached its climax with the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a triumph for President Lyndon Johnson as well as for King. Classic modes of Jim Crow racism such as segregation in theaters and bus stations would be barred under federal law.

But King and those who stood with him recognized that equality for African-Americans hinged as well on their ability to exercise a bedrock right of citizenship – the right to vote.

Keeping black residents from voting helped white minorities across the South maintain a hold on power wielded for the benefit of the privileged. When poll taxes and literacy tests didn’t deter blacks from trying to register, those would-be voters risked being beaten up or fired from their jobs. Even in communities with more blacks than whites, the number of black voters could be tiny.

The drive for equality at the polls gathered steam as civil rights workers bravely challenged the old order. Some paid with their lives.

Showdown at Selma

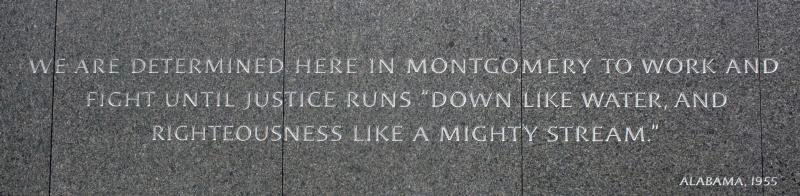

King figured prominently in what would become a pivotal episode in the voting rights campaign. He was asked by activists working to overcome voting barriers in Selma, Ala., to help organize a protest march to the state capital, Montgomery. As several hundred marchers set out along U.S. 80, they were attacked by white officers while crossing a bridge.

Many were beaten as protesters fled from the billy clubs and tear gas. News cameras caught the mayhem, and the violence of “Bloody Sunday” – March 7, 1965 – shocked the nation. A few months later, urged on by President Johnson, Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act — a legal framework meant to guarantee minority voters a say in choosing their elected leaders.

The Voting Rights Act has faced congressional scrutiny several times since then, and each time key provisions have been extended. A Supreme Court decision last year undercut the federal government’s power to oversee changes in state election laws, but the law remains a deterrent to racially biased voting rules.

It’s under the authority of the Voting Rights Act that the U.S. Justice Department now seeks to block changes by our General Assembly that will make it harder for some North Carolinians to vote.

Which North Carolinians? They’ll be people who don’t have driver’s licenses or other kinds of photo identification that most reasonably well-off citizens take for granted. They’ll be people who have trouble taking time off work to go to the polls, or who depend on others for transportation. They’ll be college students living away from home.

In other words, they’ll be people who don’t fit the mainstream, majority model – poorer than the average, older or younger, quite possibly African-American or Latino. Significantly, they tend as groups to favor Democratic candidates, which gives the Republicans who control the legislature a reason to try to hold down the number of votes they cast.

There’s no exact parallel between the legislature’s maneuverings and the vicious discrimination experienced in past decades by many black Americans who simply wanted a chance to vote. Nobody’s head has been busted, and nobody’s will be.

But in a sad echo from the era of Martin Luther King himself, people who rely on the ballot box as their only meaningful way to hold leaders to account and to try to have their concerns taken seriously now stand to have some of that influence diluted. We can be confident that King, drawing on his faith-based vision of social justice, would not have let these changes take effect without protest.

As the NC Council of Churches recently affirmed, the members of our community who are politically the weakest – typically the poor, many of whom are black – must have full and fair access to the polls. Narrowing that access for partisan gain breaches not only constitutional principles but religious ones as well. The King legacy, with voting rights at the center, offers good guidance on both scores.