The NC Council of Churches is proud to publish a brand new e-book collection of testimonies from Moral Mondays. With 32 short vignettes from North Carolinians across the state, Voices of Moral Mondays tells the story of everyday folks being motivated to speak out on account of their faith. Many, though not all, of the accounts describe what it was like to engage in civil disobedience and be arrested by the authorities. Click here to download the free e-book.

By Jay Davis, Rougemont United Methodist Church

In 1959, I graduated from Central High School in Charlotte in what I believe was the first integrated graduating class in the state. A brave young African American named Gus Roberts suffered two years of living hell to make that kind of dramatic progress for North Carolina. I was not among the students that hit him or spat on him or verbally assaulted him during that time. I, also, was not one of those who befriended him, or supported him, or stood up for him. At least once during those two years I could have said to the bullies attacking him, “Leave him alone. He is not bothering you,” but I didn’t. By my silence I, in effect, held the coats of the cruel students that daily accosted Gus. In later years I would be haunted by that silence, but, at that point in my life, my eyes were blind to the evils of prejudice and racism.

My life was about to change, however. In August of 1963, I watched Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech in my home in Charlotte. It was a profoundly affecting experience. In the words of John Wesley, “I felt my heart strangely warmed.” I knew as I listened to Dr. King’s words that I had to do something to help his dream become a reality. Looking back on that day, I am convinced that my life was almost instantaneously changed. At the risk of sounding like a religious zealot, I truly believe it was the work of the Holy Spirit.

In the fall, I returned to Appalachian State in Boone. One night during the middle of a blinding snowstorm and subfreezing weather, a friend and I were trying to catch a quick bite to eat at a local fast food place. It would only serve the local African American population from an outside service window. As we watched those miserably cold people waiting to be served, we were so offended that we demanded that they be served inside before we would eat there.

The next morning we were threatened with expulsion for trying to “turn Boone into another Chapel Hill.” That event was the first in a long series of battles I entered in the name of social justice. By the 1970s, I was married, teaching school in Delaware, and regularly making the drive to DC to protest the Vietnam War.

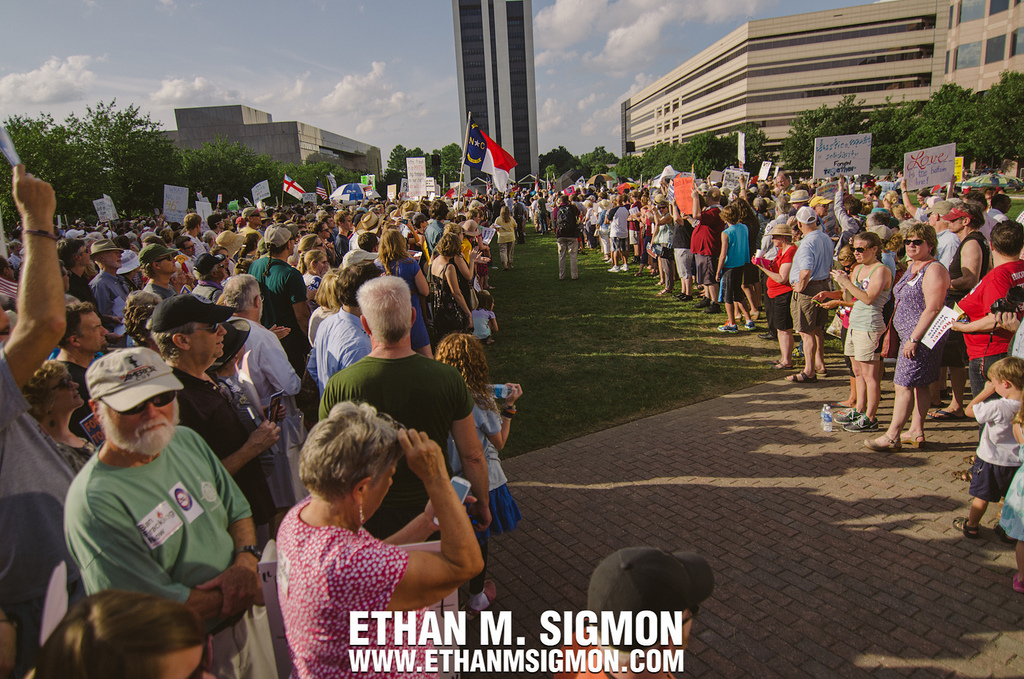

I spent most of my career as an organizer for the teachers union in New York and California. When I retired and returned to live in North Carolina, I believed I was returning to a reasonably progressive state. When the GOP began its assault on all the progress we had made in the 50 years since Dr. King’s speech, I refused to let it happen without a protest. On June 3, I joined 150 others in raising that protest at Moral Monday, and it is one of the proudest days of my life.